It rises out of the east, the sun—but it never sets on the west. I am to talk of a revolt that took place in the land of the rising sun.

Japan is a place of appreciating art. The wealthy patronize it, the makers make it. Exhibitions last for nearly a week and near about a hundred make appearance in Tokyo weekly. Children and collectors pay visits and the galleries are jammed throughout their working hours. I trust the imagery that arises in your conscience on thinking of Japanese art is something oriental, something like this:

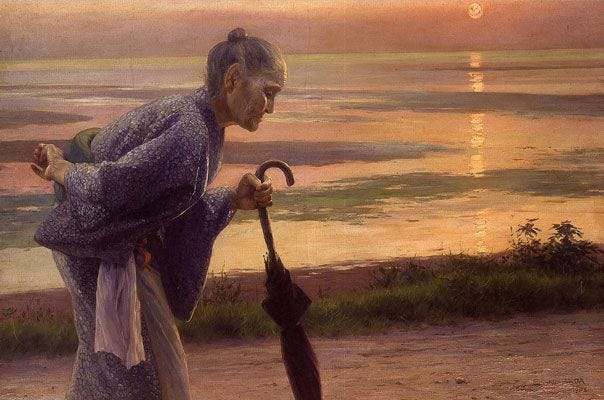

Or something close to this:

The autumn leaves. The kimono clad women. The rural Japan that highlights the country’s tradition and culture. The portraits of Fuji. Even without hearing it as you read, a very specific oriental form of music you recognize as Japanese lays in your conscience. But this pigeonhole presents but an extremely restricted miopic view of what resides in the umbrella of Japanese paintings.

What you might simply know as Japanese art is a distinct movement called the Nihonga style. Nihonga is all that you know. The term is Japanese for “pictures of Japan”. Some of the most popular and perhaps the only names you know of Japanese painters are most likely of those who mastered and strictly adhered to Nihonga. And there is a reason for the latter. And I will tell you why.

Learn that Japan's land and skies changed in the late 1800s. The country was no longer only occupied by grasslands and farmlands; the people were expanding and their customs were changing. During what is known as the Meiji period, Japan moved from a feudal and archaic civilization to adopting global advances in politics, society, and the economy. The Meiji period stimulated the country's rapid industrialization, and as society underwent a paradigm shift, the intrinsic thread of accompanying art changed its face.

The hegemonic empire of the east witnessed its obverse one-on-one. Although European style of art was introduced to Japan by missionaries in as early as the mid 16th century, the touch of western methods on Japanese art only started being visible in the 19th century and became a prominent and distinctive movement during the Meiji period. This artistic movement which encapsulated Japan in western methods of painting came to called the Yōga style.

Now, learn that Yōga art was not easily welcome in Japan. The style faced certain hostility from the established schools of traditional art. But it was not exiled into rejection just yet. One of the early terms used to refer to western-influenced Japanese art was not derived from the art’s source, i.e., the West, but rather the material abura-e—Japanese for “oil painting”.

Oil on canvas was profoundly respected and notably considered a superior style of painting against the ink or pigment on silk or paper-based traditional painting. At last, aghast, came the deranged sobriquet when, owing to the supposed threat the oil on canvas posed against Japanese pre-Meiji art, the titular abura-e (oil painting) was replaced with seiyōga or yōga (western painting) and instituted an institutionalized hostility towards an art style that had suddenly become foreign but in ways more than those known retained everything Japanese.

The hostility further lead to an all-out divide between the institutions that backed and furthered yōga and the new set of institutions that presented a firm traditional antagonism against the new threat. These called their ink on paper or silk style the Nihonga style.

These two divisions—Nihonga and Yōga developed into distinct submission categories.

The above painting is a Yōga by one of the greatest painters of this style. Have a tranquil look at the painting and your pre-conceived notion of Japanese art that was always, by this point, Nihonga. You do not pay such frequent visits to the nature and cultural mythology in Yōga as much as in the case of Nihonga.

One of the key differences between Nihonga and Yōga beyond the material used lies in the subject matter and the constancy of their appearance. In conformity with the western standards of liberalization and industrial revolution, Yōga often portrayed still life, nudes, and urban settings while retaining a sense of nipponism. Nihonga, on the other hand, sung of the native expression and traditional life of Japan.

But the divide between the two parallels widened. The binary was torn not just in painting but architecture, food, clothing, and everything that was susceptible to influence by the assorted tastes of human conscience.

The divide realized into an academic debate on which style stood best as the national identity of Japan, dismissing the once-developing notion of the distinction merely lying in the materials which the artists were free to use per their discretion.

The quest for national identity relied on which art best represented seikatsu or the ideal Japanese lifestyle true to the core. The pre-conceived notion, of course, was that Yōga was alien that ill-represented the Japanese people and Nihonga was the patriotic riposte to this degeneracy. But several artists stood to the contrary as well. Kojima Kikuo, a celebrated and revered art critic proclaimed how Japanese lifestyle was a confluence of both Western and Eastern cultures and therefore both Yōga and Nihonga represented the Japanese people best in their individual ways.

Several prominent artists of both the styles, in a survey in the year 1932, voiced their concerns over the question of national identity. Ryuzaburo Umehara—who is today considered one of the most successful flagbearers of Yōga painting—famously recorded, “It is a fallacy to think that even now you have to wear samurai armor and helmet to be a Japanese person.”

In the words of the Yōga painter Okuse Eizo, “Just as the soldiers in Manchuria with Western-style clothes and weapons make war like splendid Japanese warriors, so Western-style painting makes splendid national painting.”

In Japan’s Pacific War, both the art forms served Japan the best. Both ideas adhered to the propagandist glorification of Japan’s military missions and played distinct roles towards the same realization—justify the quest in the Pacific. Yōga put forth a heroic image of Japanese soldiers and the noble cause they fought for, whereas Nihonga sensitized this sentiment in the form of a rewind to the pastoral simplicity of the great nation that Japan was.

Over the period, the divide has surely succumbed to acceptance of a globalized world and, at the same time, a general consensus to preserve a traditional identity prone to harm by foreign influence, whichever one sees it. Children, of course, study both art forms in Japanese schools, and those who develop a career in either garner fresh exhibits in the heart of the country with virtually equal adoration for each.

Really liked your writing, didn't know of this quarrel between these art styles. Got interested in see the differences of Yōga and Nihonga in the propaganda you mentioned. I wouldn't use some terms you used for the Meiji Era, but that's just the historian in me talking. Looking forward to read more of your texts!