Art is often presented as an amalgamating force of distinct portrayals and narratives that brings all cracks together but the history of the medium has seldom spoken of such character. The progression of art has been observed to have branched from epochs of exclusion and disengagement. The moral worth of art for schisms that had been done with seeing one another was continuously evaluated for the eyes of the noble and perspectively upright.

Born upper-class in 1848, the French Gustave Caillebotte was a champion of the impressionist movement in France. Caillebotte studied law and was also an engineer before he decided to finally dedicate his effort to art.

For openers, the Impressionist movement originated when several young French painters rebelled against the Académie's artistic standards. The Académie des Beaux-Arts was the main artistic association in nineteenth-century France, and it envisioned the famed yearly exhibition Salon de Paris. Every ambitious painter of the time ached to exhibit at the Salon seeing it would bring them renown, commissions, and exceptional repute.

Regardless, the Salon had an identifiable tend. The jury's norms frequently showed a strict and conservative view to the dynamic relay of art. Favouritism buried deep within the Salon crevices, which elevated antique and legendary theme art to an accepted higher pedestal than paintings on other subjects. The Salon welcomed painters who created escapist art that depicted a utopian, flawlessly beautiful world immersed in mythological and classical retellings of European history embedded in ancient Greece and other stories that were far removed from contemporary depictions of reality and modern utility.

On the strength of this, a handful modern artists who repudiated the Salon's unreasonable commitment to idealization and fallacies had an identical goal: to depict the reality of human life. They abandoned fictitious and classical depictions in favor of capturing the beauty of landscapes and daily life. These painters, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille, used their paintings to convey the delicacy of the en plein air—French for "outdoors"—style of art.

The paintings made by these artists were frequently rejected by the Salon jury, who rated their techniques, subjects of regular life, styles, and themes unsuitable of an exhibit. And as a result of their dissatisfaction and demand for creative independence, the impressionists—as they came to be known—split from the Académie and created the Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs in 1873 to exhibit their art independently.

Gustave Caillebotte, who was still a newcomer to France's artistic setting at the time, attended the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and, after becoming involved with the rebel group later that year, made his debut in the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876, where he displayed eight of his own creations.

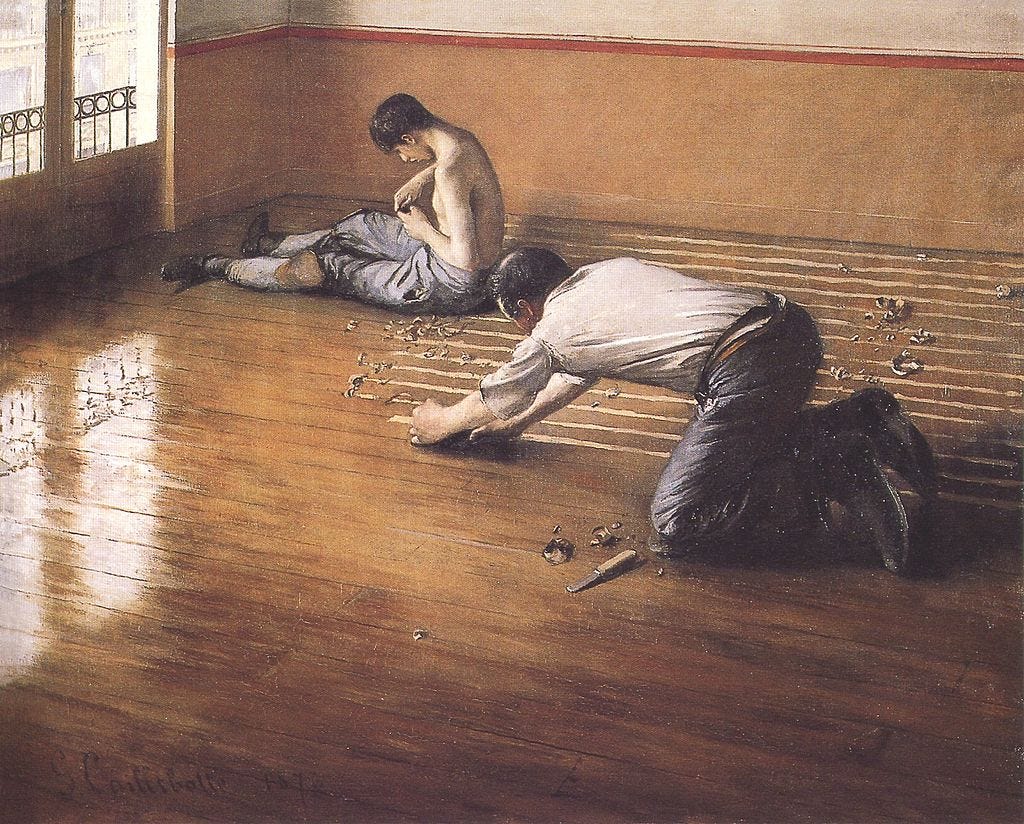

Of these eight, one held the title Les raboteurs de parquet (The Floor Scrapers), one of his earliest works.

Before displaying it at the second Impressionist exhibition, Caillebotte sought to submit it at the Salon, which the organization's jury not only discarded but also condemned as having a "vulgar subject matter". The jurors' imagined vulgarity, dare I say it, lay in the painting's out and crude nudity of working-class individuals.

The jury's conduct stemmed from their amazement at the subject matter, which depicted laborers scraping a hardwood floor—an a shared spectacle for the working class, which made up the vast majority of the French population. Confirming its predisposition to not consider everyday subjects worthy of presentation alongside "high art" of historical and mythological character, the Salon and other adherents of the tradition greeted the painting with varied reactions.

One of the biggest critics of Impressionism, Emile Porchoron said thus about the painting:

“The least bad of the exhibition. One of the missions Impressionism seems to have set for itself is to torture perspective: you see here what results can be obtained.”

Another one named Louis Enault came off relatively mild but did no betrayal to his clinging over art that portrays perfection—no matter how unrealisitically:

“The subject matter is certainly vulgar, but we can understand how it might tempt a painter. I only regret that the artist did not choose his types better... The arms of the planers are too thin, and their chests too narrow... may your nude be handsome or don't get involved with it!”

Émile Zola said thus:

“An anti-artistic painting, painting as neat as glass, bourgeois painting, because of the exactitude of the copying.”

The critics who held to conventional approaches presented the common denominator of being unable to be delighted by work that, in their opinion, was not representative of imagination and idealization but rather simply documented a people, similar to photographs. But is there any credible weight on that view?

In this forum, I typically defer the final judgment to the readers, but this time, I take a firm stand. Let it be clear: the artistic portrayal of everyday human life warrants nothing short of unreserved admiration. It not only immortalizes the people—those whose labor forms the livable world as we see it—but also strikes a bold, unapologetic blow against the long-standing academic elitism that has, for too long, reserved the pedestal of art for the lofty and the aristocratic. This art, in all its raw authenticity, challenges the very foundations of institutions that once deemed only the highborn and their narratives worthy of recognition, proclaiming instead the profound value of the ordinary, the real, and the human.

After being rejected, but before exhibiting his final piece at the second Impressionist exhibition, he painted a second version of the same subject—almost as if signaling his revolt against the Salon's absurd concept and a message that art of the "ordinary" cannot cease to exist.

Renoirs treatment of the subjects eyes .. darkened orbital areas, all the same!

Bravo! I'm never opposed to learning more about the history of art. I'll follow that by saying your writing voice is clear--it allows for fuller understanding and draws the reader in. That's not common. Keep creating.