The forthcoming year awaits and so we welcome you to read of the years foregone. Welcome one and all to the twenty eighth volume of The Archaic Allegory where history is brought in intention and is anointed with madness.

Enough with the literature, mythology, and people. For the three can only carry you so far, and the dimensions beyond are hidden in the structures and styles that envelop us. This week, we'll brew about the bewildering miracles of human achievement, without which earthly life would veer into an awful unreasonableness, an abysmal sorrow.

For the heavens would sob had there been no caressing edifices, and the soil would wail, such as the Indian sitar, if there ceased to remain a penetration of brick and mortar.

They showcased the regions they ruled, the impregnable armies at beck and call, their enchanting wives and their surma, their lineage tracing back to the Mongols, resounding melodies, and opulent royal halls. Yet, amidst these grand displays, the Mughals seldom forgot their manifest gardens.

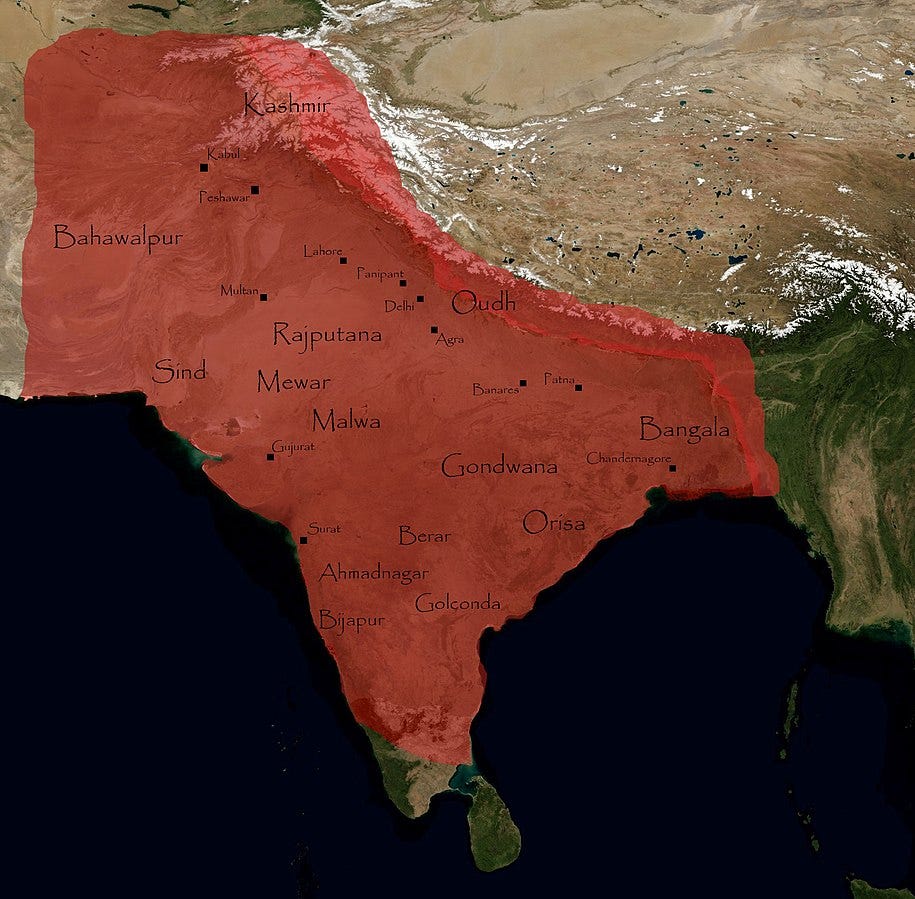

The Mughals were an Islamic dynasty that reigned over extensive portions of south Asia and the Indian subcontinent at the height of their power, arguably more than any other monarchy in the region ever could. The dynasty traced its origins back to the Mongols—from whence the moniker Mughal was derived—and Timur, the monarch of Iran and Iraq.

Leaving aside their works and horrors, the Mughals left an indelible impression on Indian soil in the shape of the vivid tastes and colors of a foreign blood accepted in native life in the form of their architecture that adorned an Indianness sooner than one could imagine.

The Mughals were especially appreciative of expanding their tremendous gardens over acquired lands. Mughal gardens, as they are now known, are covertly laid out over domains spanning from Afghanistan to Bangladesh, with India and Pakistan constituting the medians.

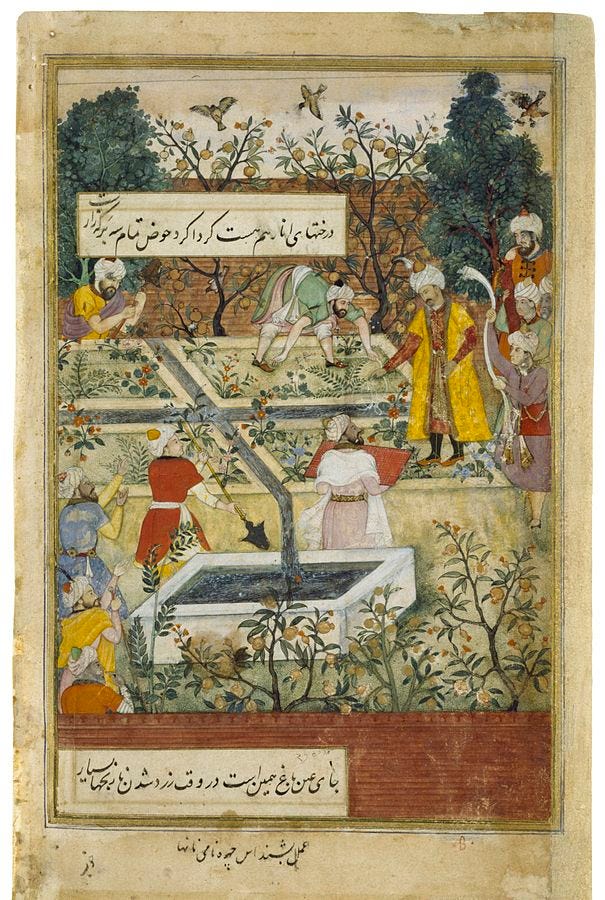

The first Mughal emperor Babur introduced this Persian art form to India. He called his favorite gardens charbagh, a combination of the words "char" (four) and "bagh", which mean "garden". This term describes Babur's favourite arrangement of lawns in four parts.

In this layout, four lawns appear around the estate, separated by walkways or irrigation systems, with the main structure generally in the center.

This concept emerged in India in the wake of an impulse to reproduce the art at home that was originally seen at the Afghan capital Kabul's Bagh-e-Babur, where Babur was raised. Soon after, the concept was adopted with an Indian tinge and widely reproduced across the subcontinent.

The notion that sought Babur's desire is inspired by the holy Qur'an, which portrays the four gardens of Paradise as follows:

And for him, who fears to stand before his Lord, are two gardens.

And beside them are two other gardens.

Babur, more than any other Mughal ruler who came after him, became preoccupied with the premise of the charbagh. He oversaw directly the construction projects that would create the leisure grounds of his aspirations.

What is never instantly and clearly visible, especially by means of photographs but also during practical visits, is that virtually all Mughal charbagh gardens were designed on minor slopes to let water flow naturally and effortlessly irrigate the gardens. The main building at the centre, or sometimes a mere pavilion, where the streams converged, used to be a tank that used gravity alone to irrigate the gardens all around.

Following Babur, the aspiration for charbaghs experienced a prolonged hiatus due to his successor Humayun, who, unlike Babur, did not contribute significantly to architectural wonders. This was not because he lacked the inclination but rather because he was extensively engaged in warfare.

Humayun faced the challenge of losing the empire to the Suri dynasty, and it took him 15 years of relentless struggle and warfare to reclaim it. Consequently, his focus on military affairs impeded the development of elaborate gardens and architectural projects during his reign.

Yet, without Humayun's successful reclamation of the Mughal empire, none of the subsequent achievements would have been conceivable. Therefore, while he may not have directly influenced Mughal architecture, his pivotal role was arguably the most crucial in the grand scheme of things.

Following Humayun, the eras of his son Akbar and great-grandson Shah Jahan stand out as remarkable chapters in Mughal architecture across the Indian subcontinent. During their reigns, charbaghs were meticulously crafted with dual objectives in mind: serving as leisurely retreats for the royal family and functioning as ornate gardens surrounding the tombs of previous emperors.

As mentioned earlier, the key structures within these gardens were either reservoirs or the final resting places of significant figures from the royal family or administration. For instance, the mausoleum of Safdar Jung, a prominent Mughal prime minister in Delhi, showcases a raised platform upon which the tomb is constructed. This platform boasts its own array of architectural and decorative wonders in the distinctive style of the Mughal era, positioned at the heart of the charbagh.

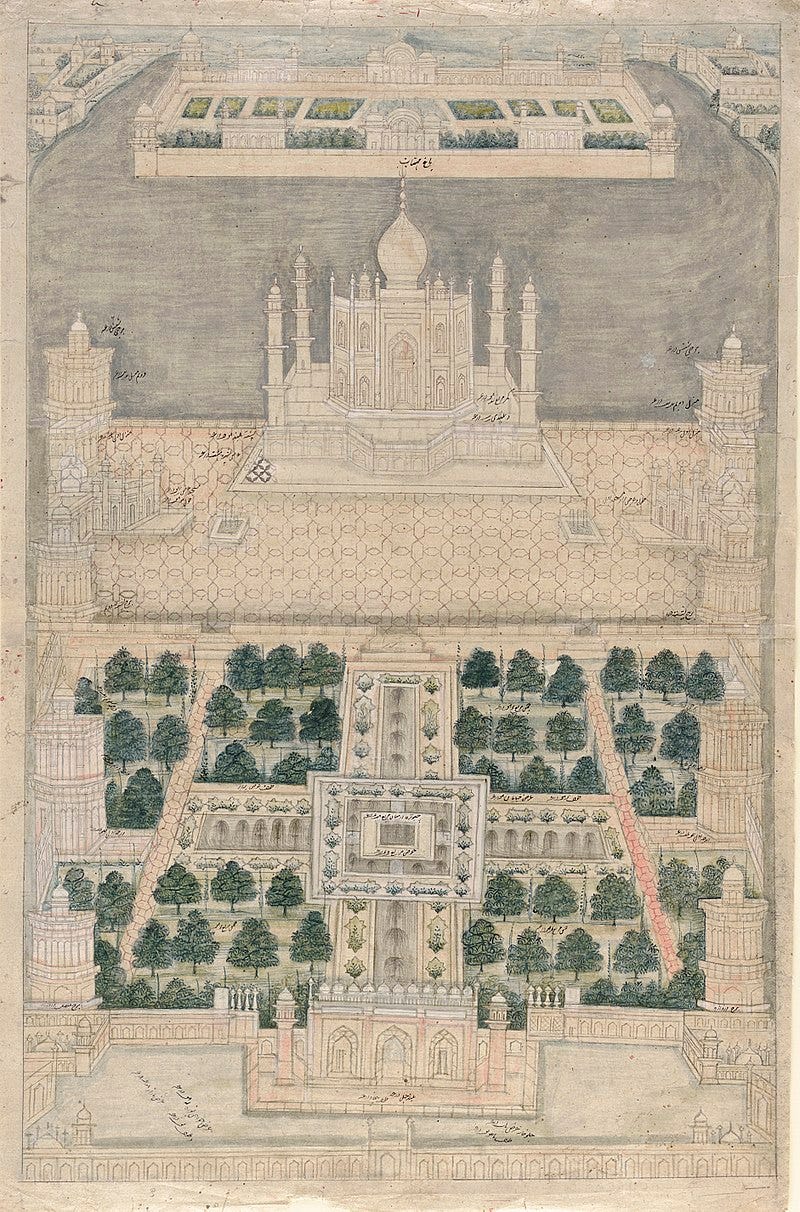

Emperor Shah Jahan dedicated the creation of the Taj Mahal to the memory of his cherished wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and enveloped it with the enchanting Mehtab Bagh, a series of elaborate gardens. The landscape is embellished with cascades, presenting an uninterrupted array of magnificent plants and trees, providing a captivating experience for all who visit the icon of India.

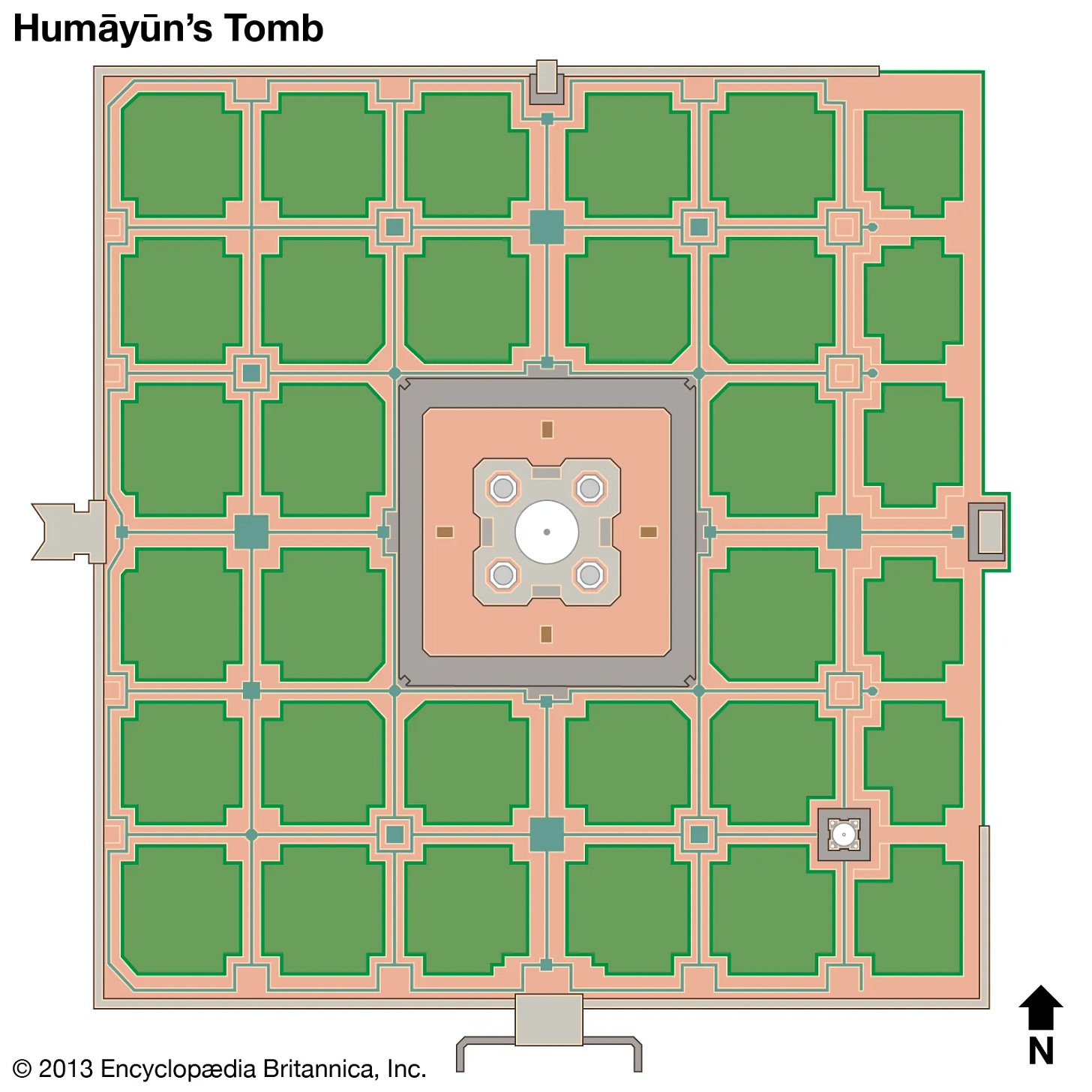

Two distinct architectural styles emerge in the Mughal conception of a charbagh, although the motivations behind them are primarily rooted in aesthetics rather than functional or contextual considerations for the central building. The first approach involves placing the building, typically a tomb or a leisure terrace, at the center of the charbagh, making it the focal point while the gardens serve as embellishing backdrops. In contrast, the second approach positions the main building at the head of the gardens, not merely as a backdrop but as an integral element, with no apparent distinction between the surroundings and the tomb itself.

In the image below, the architectural plan of Humayun's Tomb features an elaborate structure positioned at the heart of the gardens where the pathways converge.

The illustration below provides a bird’s eye view of the Taj Mahal, wherein the primary structure, namely the Taj, is situated at the head of the gardens. In this case, the gardens boast equal significance to the monument itself, eliminating the notion of serving merely as a backdrop, as previously noted.

The idea underlying charbagh construction, as it is now known, was to depict a gracious concord between the destructive human existence and the inviting nature. Many of these Mughal gardens were found with fountainry and notable water terraces, which would take on a distinct charm if situated in regions where winter brought a frosty touch.

Shalimar Bagh in Kashmir, once more commissioned by Shah Jahan, irrigates poetry to to its pavements. Life within these gardens was anything but dreary; quite the opposite, I must say. The royal family devoted significant portions of their days seeking refuge in the charbaghs, the four-parted gardens meticulously crafted for their enjoyment.

The pavilion at Shalimar conveys an inscription from Persian poet Urfi Shirazi that says:

اگر فردوس بر روے زمین است

همین است و همین است و همین است

Agar Firdaus bar rōy-e zamin ast,

hamin ast-o hamin ast-o hamin ast.

which literally translates to:

If there is a paradise on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here.

Here’s a piece of poetry written by Muriel A.E. Brown about the Shalimar gardens in 1921:

Shalimar! Shalimar!

A rhythmic sound in thy name rings

A dreamy cadence from afarWithin those syllables which sings

To us of love and joyous days

Of Lalla Rukh! of pleasure feast!

Of fountains clear whose glitt’ring sprays

Drawn from the snows have never ceasedTo cast their spell on all who gaze

Upon this handiwork of love

Eared in Jehangir’s proudest daysHomage for Nur Mahal to prove.

For his fair Queen he built these courts

With porphyry pillars smooth and blackWhose grandeur still expresses thoughts

For her that should no beauty lack.The roses show ‘ring o’er these walls

Still fondly whisper love lurks hereAnd still he beckoning to us calls

By yon Dai’s shores in fair Kashmir.

Numerous Mughal gardens stand today as living canvases, showcasing the imprint of a distant culture embraced by India, etched into the vast remembrance of its historical memory. These gardens echo a saga of power and intrigue, as poignant reminders of the immense journey the subcontinent has traversed, all the while retaining the intricate roots that refuse to fade into oblivion.

This concludes the exploration of the initial architectural issue at The Archaic Allegory. I will be embarking on personal visits to several of these charbaghs later this month.

Ladies and gentlemen, let us remember that what we construct is a reflection of what we hold dear. Since the inception of our presence on this enigmatic planet, humans have been builders, and delving into the notions and motivations they have cherished is a captivating endeavor—a truly beautiful one, indeed.

Until next week, this is The Archaic Allegory, signing off.